Safety of NFCFs (Sustainability Assessment)

INPRO basic principle (BP) for sustainability assessment in the area of NFCF safety - The planned NFCF is safer than the reference NFCF. In the event of an accident, off-site releases of radionuclides and/or toxic chemicals are prevented or mitigated so that there will be no need for public evacuation.

Contents

Introduction

Objective

This volume of the updated INPRO manual provides guidance to the assessor of a planned NES (or a facility) on how to apply the INPRO methodology in the area of NFCF safety. The INPRO assessment is expected either to confirm the fulfilment of all INPRO methodology NFCF criteria, or to identify which criteria are not fulfilled and note the corrective actions (including RD&D) that would be necessary to fulfil them. It is recognized that a given Member State may adopt alternative criteria with indicators and acceptance limits that are more relevant to its circumstances. Accordingly, the information presented in Chapters 5 to 10 (INPRO methodology criteria, user requirements and basic principle for sustainability assessment in the area of safety of NFCFs) should be viewed as guidance. However, the use of such alternative criteria should be justified as providing an equivalent level of enhanced safety as the INPRO methodology.

This report discusses the INPRO sustainability assessment method for the area of safety of NFCFs. The INPRO sustainability assessment method for safety of nuclear reactors is discussed in a separate report of the INPRO manual .

This publication is intended for use by organizations involved in the development and deployment of a NES including planning, design, modification, technical support and operation for NFCF. The INPRO assessor (or a team of assessors) is assumed to be knowledgeable in the area of safety of NFCFs and/or may be using the support of qualified national or international organizations (e.g. the IAEA) with relevant experience. Two general types of assessors can be distinguished: a nuclear technology holder (i.e. a designer, developer or supplier of nuclear technology), and a (potential) user of such technology. The role of a technology user in an INPRO assessment is to check in a simplified way whether the supplier’s facility design appropriately accounts for nuclear safety related aspects of long term sustainability as defined by the INPRO methodology. A designer (developer) can use this guidance to check whether a new design under development meets the sustainability focused INPRO methodology criteria in the area of fuel cycle safety and can additionally initiate modifications during early design stages if necessary to improve the safety level of the design. The current version of the manual includes a number of explanations, discussions, examples and details so it is deemed to be used by technology holders and technology users.

Scope

This manual provides guidance for assessing the sustainability of a NES in the area of NFCF safety. This report deals with NFCFs that may be potentially involved in the NES, i.e. mining, milling , refining, conversion, enrichment, fuel fabrication, spent fuel storage, and spent fuel reprocessing facilities. It is clear that operations of NFCFs are more varied in their processes and approaches than are nuclear reactor systems. Most significant of these variations is the fact that some countries pursue an open fuel cycle, i.e. spent fuel is treated as a waste, while some others have a policy of closing the fuel cycle, i.e. treating the spent fuel as a resource, and a number of states have yet to make a final decision on an open or closed fuel cycle. Further, diversity is large if one considers different types of fuels used in different types of reactors and the different routes used for processing the fuels before and after their irradiation depending upon the nature of the fuel (e.g. fissile material: low enriched uranium/ natural uranium/ uranium-plutonium/ plutonium/ thorium; fuel form: metal/ oxide/ carbide/ nitride) and varying burnup and cooling times. Taking into account this complexity and diversity, the approach adopted in this report has been to deal with the issues as far as possible in a generic manner, rather than describing the operations that are specific to certain fuel types. This approach has been chosen in order to arrive at a generalized procedure that enables the user of this report (the assessor) to apply it with suitable variations as applicable to the specific fuel cycle technology being assessed. In addition, it is recognized that the defence in depth (DID) approach and ultimate goal of inherent safety form the fundamental tenets of safety philosophy. The DID approach is applied to the specific safety issues of NFCFs.

As the safety issues relevant to the sustainability assessment of refining and conversion facilities are similar to those of enrichment facilities, the INPRO methodology criteria for those two types of facilities are combined in this manual and not discussed separately. Based on similar considerations, the assessments of uranium and uranium-plutonium mixed oxide (MOX) fuel fabrication facilities have likewise been combined . However, particular care must be taken to ensure that using a graded assessment approach and enhanced safety measures for higher risk facilities (e.g. using plutonium or uranium with higher enrichments/criticality risks) will yield appropriately enhanced levels of safety.

It should be noted that for NFCFs the INPRO methodology includes the consideration of chemical and industrial safety issues, principally where these could affect facility integrity or radiological safely. Although otherwise beyond the scope of this guidance, it bears noting that care is required due to the different public perceptions of the risks posed by conventional and radiological events and releases and, conversely, the negative reactions that may be generated about an NFCF’s radiological safety if conventional safety events occur.

In the current version of the INPRO methodology, the sustainability issues relevant to safety of reactors and safety of NFCFs are considered in different areas. Innovative integrated systems combining reactors, fuel fabrication and reprocessing facilities on the same site such as molten salt reactors with nuclear fuel in liquid form and integrated fast reactors with metallic fuel has not been specifically addressed. Reactor and NFCF installations of such integrated systems are expected to be assessed simultaneously and independently against corresponding criteria in the INPRO areas of reactor safety and safety of NFCFs. When more detailed information on the safety issues in integrated systems has been acquired, this approach can be changed in the next revisions of the INPRO methodology.

NFCFs processing nuclear materials in a given stage of the fuel cycle may be based on different technologies with different safety issues. Different kinds of fuel may be fabricated or reprocessed in different facilities serving different reactors. In this report, the discussion is restricted to the fabrication of fuels most commonly used in power reactors; however, the requirements and criteria have been formulated in a sufficiently generic manner and are therefore expected to be applicable to innovative technologies. Nevertheless, the fabrication or reprocessing technologies for innovative types of fuels (e.g. TRISO fuel with carbon matrix, metal fuel, nitride fuel) may involve safety issues requiring the modification of specific INPRO methodology criteria or the introduction of new or complementary criteria. It is expected that the future accrual of more detailed information on safety issues in innovative NFCFs will give rise to proposed modifications of the INPRO criteria and that these will be considered in future revisions of the methodology.

In this version of the INPRO methodology, the transportation of fresh nuclear fuel, spent nuclear fuel, and other radioactive materials or wastes throughout the nuclear fuel cycle has not been generally considered as independent stages of the nuclear fuel cycle. The INPRO methodology does not define specific requirements and criteria for such transportation but assumes that the safety issues of transportation are to be considered as part of the INPRO assessments of those NFCFs from which such packaging and transportation activities originate, e.g. fuel fabrication facilities for fresh fuel transportation and spent fuel storage facilities for spent fuel transportation. The IAEA has developed a set of safety standards to establish requirements and recommendations that need to be satisfied to ensure safety and to protect persons, property and the environment from the effects of radiation in the transport of radioactive material[1][2][3][4][5][6].

This manual does not establish any specific safety requirements, recommendations or criteria. The INPRO methodology is an internationally developed metric for measuring nuclear energy system sustainability and is intended for use in support of nuclear energy system planning studies. IAEA safety requirements and guidance are only issued in the IAEA Safety Standards Series. Therefore, the basic principles, user requirements and associated criteria contained in the INPRO methodology should only be used for sustainability assessments. The INPRO methodology is typically used by Member States in conducting a self-assessment of the sustainability and sustainable development of nuclear energy systems. This manual should not be used for formal or authoritative safety assessments or safety analyses to address compliance with the IAEA Safety Standards or for any national regulatory purpose associated with the licensing or certification of nuclear facilities, technologies or activities.

The manual does not provide guidance on implementing fuel cycle safety activities in a country. Rather, the intention is to check whether such activities and processes are (or will be) implemented in a manner that satisfies the INPRO methodology criteria, and hence the user requirements and the basic principle for sustainability assessment in the area of safety of NFCFs.

Structure

This publication follows the relationship between the concept of sustainable development and different INPRO methodology areas. Section 2 describes the linkage between the United Nations Brundtland Commission’s concept of sustainable development and the IAEA’s INPRO methodology for assessing the sustainability of planned and evolving NESs. It further describes general features of NFCF safety and presents relevant background information for the INPRO assessor. Section 3 identifies the information that needs to be assembled to perform an INPRO assessment of NES sustainability in the area of NFCF safety. Section 4 identifies the different types of facilities that can form part of a nuclear fuel cycle. This section also provides an overview of the general safety aspects of those facilities. Section 5 presents the rationale and background of the basic principle and user requirements for sustainability assessment in the INPRO methodology area of NFCF safety. Criteria are then presented in Sections 6 to 10 along with a procedure at the criterion level for assessing the potential of each NFCF to fulfil the respective INPRO methodology requirements. The Annex presents a brief overview of the selected IAEA Safety Standards for NFCFs that are the basis of the INPRO methodology in this area. The Annex also explains the relationship and differences between the IAEA Safety Standards and the INPRO methodology. Table 1 provides an overview of the basic principle and user requirements for sustainability assessment in the area of NFCF safety.

| NPRO basic principle for sustainability assessment in the area of NFCF safety: The planned NFCF is safer than the reference NFCF. In the event of an accident, off-site releases of radionuclides and/or toxic chemicals are prevented or mitigated so that there will be no need for public evacuation. | |

| UR1: Robustness of design during normal operation | The assessed NFCF is more robust than the reference design with regard to operation and systems, structures and components failures. |

| UR2: Detection and interception of AOOs | The assessed NFCF has improved capabilities to detect and intercept deviations from normal operational states in order to prevent AOOs from escalating to accident conditions. |

| UR3: Design basis accidents (DBAs) | The frequency of occurrence of DBAs in the assessed NFCF is reduced. If an accident occurs, engineered safety features and/or operator actions are able to restore the assessed NFCF to a controlled state, and subsequently to a safe state, and the consequences are mitigated to ensure the confinement of radioactive and/or toxic chemical material. Reliance on human intervention is minimal, and only required after sufficient grace period. |

| UR4: Severe plant conditions | The frequency of an accidental release of radioactivity into the environment is reduced. The source term of accidental release into the environment remains well within the envelope of the reference facility source term and is so low that calculated consequences would not require public evacuation. |

| UR5: Independence of DID levels and inherent safety characteristics | An assessment is performed to demonstrate that the DID levels are more independent from each other than in the reference design. To excel in safety and reliability, the assessed NFCF strives for better elimination or minimization of hazards relative to the reference design by incorporating into its design an increased emphasis on inherently safe characteristics. |

| UR6: Human factors (HF) related to safety | Safe operation of the assessed NFCF is supported by accounting for HF requirements in the design and operation of the facility, and by establishing and maintaining a strong safety culture in all organizations involved in the life cycle of the facility. |

| UR7: RD&D for advanced designs | The development of innovative design features of the assessed NFCF includes associated research, development and demonstration (RD&D) to bring the knowledge of facility characteristics and the capability of analytical methods used for design and safety assessment to at least the same confidence level as for operating facilities. |

This section presents the relationship of the INPRO methodology with the concept of sustainable development, a comparison of NFCFs with chemical plants and nuclear reactors, and a summary of INPRO recommendations on the application of the DID concept to NFCFs.

The concept of sustainable development and its relationship with the INPRO methodology in the area of NFCF safety

The United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development Report [7](often called the Brundtland Commission Report), defines sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (para.1). Moreover, this definition:

“contains within it two key concepts:

- the concept of ‘needs’, in particular the essential needs of the world’s poor, to which overriding priority should be given; and

- the idea of limitations imposed by the state of technology and social organization on the environment’s ability to meet present and future needs.”

Based on this definition of sustainable development a three-part test of any approach to sustainability and sustainable development was proposed within the INPRO project: 1) current development should be fit to the purpose of meeting current needs with minimized environmental impacts and acceptable economics, 2) current research, development and demonstration programmes should establish and maintain trends that lead to technological and institutional developments that serve as a platform for future generations to meet their needs, and 3) the approach to meeting current needs should not compromise the ability of future generations to meet their needs.

The definition of sustainable development may appear obvious, yet passing the three-part test is not always straightforward when considering the complexities of implemented nuclear energy systems and their many supporting institutions. Indeed, many approaches may only pass one or perhaps two parts of the test in a given area and fail the others. Where deficiencies are found, it is important that appropriate programmes be put in place to meet all test requirements to the extent practicable. Nevertheless, in carrying out an NFCF INPRO assessment, it may be necessary to make judgements based upon incomplete knowledge and to recognize, based upon a graded approach, the variable extent of the applicability of these tests for a given area.

The Brundtland Commission Report’s overview (para.61 in Ref[7]) on nuclear energy summarized the topic as follows:

The Brundtland Commission Report presented its comments on nuclear energy in Chapter 7, Section III. In the area of nuclear energy, the focus of sustainability and sustainable development is on solving certain well known problems (referred to here as ‘key issues’) of institutional and technological significance. Sustainable development implies progress and solutions in the key issue areas. Seven key issues are discussed:

- Proliferation risks;

- Economics;

- Health and environment risks;

- Nuclear accident risks;

- Radioactive waste disposal;

- Sufficiency of national and international institutions (with particular emphasis on intergenerational and transnational responsibilities);

- Public acceptability.

The INPRO methodology for self-assessing the sustainability and sustainable development of a NES is based on the broad philosophical outlines of the Brundtland Commission’s concept of sustainable development described above. Although three decades have passed since the publication of the Brundtland Commission Report and eighteen years have passed since the initial consultancies on development of the INPRO methodology in 2001 the definitions and concepts remain valid. The key issues for sustainable development of NESs have remained essentially unchanged over the intervening decades, although significant historical events have starkly highlighted some of them.

During this period, several notable events have had a direct bearing on nuclear energy sustainability. Among these were events pertaining to non-proliferation, nuclear security, waste management, cost escalation of new construction and, most notably, to nuclear safety.

Each INPRO methodology manual examines a key issue of NES sustainable development. The structure of the methodology is a hierarchy of INPRO basic principles, INPRO user requirements for each basic principle, and specific INPRO criteria for measuring whether each user requirement has been met. Under each INPRO basic principle for the sustainability assessment of NESs, the criteria include measures that take into consideration the three-part test based on the Brundtland Commission’s definition of sustainable development as described above.

The Commission Report noted that national governments were responding to nuclear accidents by following one of three general policy directions:

“National reactions indicate that as they continue to review and update all the available evidence, governments tend to take up three possible positions:

- remain non-nuclear and develop other sources of energy;

- regard their present nuclear power capacity as necessary during a finite period of transition to safer alternative energy sources; or

- adopt and develop nuclear energy with the conviction that the associated problems and risks can and must be solved with a level of safety that is both nationally and internationally acceptable.”

These three typical national policy directions remain consistent with practice to the current day. Within the context of a discussion on sustainable development of nuclear energy systems, it would seem that the first two policy positions cannot result in development of a sustainable nuclear energy system in the long term since nuclear energy systems are either avoided altogether or phased out over time. However, it is arguable that both policy approaches can meet the three-part Brundtland sustainable development test if technology avoidance or phase-out policies are designed to avoid foreclosing or damaging the economic and technological opportunity for future generations to change direction and start or re-establish a nuclear energy system. This has certain specific implications regarding long term nuclear education, knowledge retention and management and with regard to how spent nuclear fuels and other materials, strategic to nuclear energy systems, are stored or disposed of.

The third policy direction proposes to develop nuclear energy systems that “solve” the problems and risks through a national and international consensus approach to enhance safety. This is a sustainable development approach where the current generation has decided that nuclear energy is necessary to meet its needs, while taking a positive approach to develop enhanced safety to preserve the option in the future. In addition to the general outlines of how and why nuclear reactor safety is a principal key issue affecting the sustainability and sustainable development of nuclear energy systems, the Commission Report also advised that several key institutional arrangements should be developed. Since that time, efforts to establish such institutional arrangements have achieved a large measure of success. The Brundtland Commission Report was entirely clear that enhanced nuclear safety is a key element to sustainable development of nuclear energy systems. It is not possible to measure nuclear energy system sustainability apart from direct consideration of certain safety issues.

Understanding the psychology of risk perception in the area of nuclear safety is critical to understanding NES sustainability and sustainable development. In a real measured sense, taking into account the mortality and morbidity statistics of other non-nuclear energy generation technology chains (used for similar purpose), nuclear energy has an outstanding safety record, despite the severe reactor accidents that have occurred. However, it should not be presumed that this means that reactor safety is not a key issue affecting nuclear energy system sustainability. How do dramatically low risk estimations (ubiquitous in nuclear energy system probabilistic risk assessment) sometimes psychologically disguise high consequence events in the minds of designers and operators, while the lay public perception of risk (in a statistical sense) may be tilted quite strongly either toward supposed consequences of highly unlikely, but catastrophic disasters, or toward a complacent lack of interest in the entire subject? This issue has been studied for many years. What should be the proper metrics for the INPRO sustainability assessment methodology given that the technical specialist community has developed an approach that may seem obscure and inaccessible to the lay public?

With regard to nuclear safety, the public are principally focussed on the individual and collective risks and magnitude of potential consequences in case of accidents (radiological, economic and other psychosocial consequences taken together). In the current INPRO manual, the URs and CRs focus on assessment of the NES characteristics associated with the majority of these issues. Unlike several other key sustainability issues assessed in other areas of the INPRO methodology, Brundtland sustainability in the area of nuclear safety is intimately tied to public perception of consequence and risk. Continuously allaying public concern about nuclear reactor safety is central to sustainability and sustainable development of nuclear energy systems.

This report describes how to assess NES sustainability with respect to the safety of NFCFs.

How NFCFs compare with nuclear reactors and chemical plants

As stated in Section 3 of Ref[8], NFCFs imply a great diversity of technologies and processes. They differ from nuclear power plants (NPPs) in several important aspects, as discussed in the following paragraphs.

First, fissile materials and wastes are handled, processed, treated, and stored throughout NFCF mostly in dispersible (open) forms. Consequently, materials of interest to nuclear safety are more distributed throughout NFCF in contrast to NPP, where the bulk of nuclear material is located in the reactor core or fuel storage areas. For example, nuclear materials in current reprocessing plants are present for most or part of the process in solutions that are transferred between vessels used for different parts of the processes, whereas in most NPPs nuclear material is present in concentrated form as solid fuel.

Second, NFCFs are often characterized by more frequent changes in operations, equipment and processes, which are necessitated by treatment or production campaigns, new product development, research and development, and continuous improvement.

Third, the treatment processes in most NFCFs use large quantities of hazardous chemicals, which can be toxic, corrosive and/or combustible.

Fourth, the major steps in NFCFs consist of chemical processing of fissile materials, which may result in the inadvertent release of hazardous chemicals and/or radioactive substances, if not properly managed.

Fifth, the range of hazards in some NFCFs can include inadvertent criticality events, and these events can occur in different locations and in association with different operations.

Finally, in NFCFs a significantly greater reliance is placed on the operator, not only to run a facility during its normal operation, but also to respond to anticipated operational occurrences and accident conditions [9].

Whereas the reactor core of an NPP presents a very large inventory of radioactive material and coolant at high temperature and pressure and within a relatively small volume, the current generation of NFCFs operate at near ambient pressure and temperature and with comparatively low inventories at each stage of the overall process. Accidents in NFCFs may have relatively low consequences when compared against nuclear power plants. Exceptions to this are facilities used for the large scale interim storage of liquid fission products separated from spent fuel and, where applicable, facilities for separating and storing plutonium.

In some cases in an NFCF, there are rather longer timescales involved in the development of accidents and less stringent process shutdown requirements are necessary to maintain the facility in a safe state, as compared to an NPP. Nevertheless, the INPRO area of NFCF safety applies the principles of the DID concept and encourages the NFCF designers to enhance the independence of DID levels in new facilities. NFCFs also often differ from NPPs with respect to the enhanced importance of ventilation systems in maintaining their safety even under normal operation. This is because nuclear materials in these facilities are in direct contact with ventilation or off-gas systems. Various forms and types of barriers between radioactive inventories and operators may have different vulnerabilities. Fire protection and mitigation assume greater importance in an NFCF due to the presence of larger volumes of organic solutions and combustible gases. With fuel reprocessing or fuel fabrication facilities, the wide variety of processes and material states such as liquids, solutions, mixtures and powders needs to be considered in safety analysis.

From this point of view, the safety features of NFCFs are often more similar to chemical process plants than those of NPPs. In addition, radioactivity and toxic chemical releases and criticality issues warrant more attention in NFCFs than in NPPs . Further comparisons of the relevant features of an NPP, a chemical process plant and an NFCF are presented in Table 2.

| Feature | NPP | Chemical Process Plant | NFCF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of hazardous materials | Mainly nuclear and radioactive materials | A variety of materials dependent on the plant (acids, toxins, explosives, combustibles, etc.) | - Nuclear and radioactive materials; - Acids, toxins, combustibles (nitric acid, hydrogen fluoride, solvents, process and radiolytic hydrogen, etc.) |

| Areas of hazardous sources and inventories | - Localized in core, fuel storage and spent fuel pool; - Standardized containment system, cooling of residual heat, criticality management |

Distributed in the process and present throughout the process equipment | - Present throughout the process equipment in the facility; - Consisting both of nuclear materials and chemically hazardous materials; |

| Physical forms of hazardous materials (at normal operation) | - Fuel in general is in solid form ; - Other radioactive materials in solid, liquid, gaseous form |

Wide variety of physical forms dependent on the process, e.g. solid, liquid, gas, slurry, powder | - Wide variety of physical forms of nuclear and radioactive materials; - Wide variety of physical forms of chemically hazardous materials |

As outlined above, from a safety point of view, NFCFs are characterized by a variety of physical and chemical treatments applied to a wide range of radioactive materials in the form of liquids, gases and solids. Accordingly, it is necessary to incorporate a correspondingly wide range of specific safety measures in these activities. Radiation protection requirements for the personnel are more demanding, especially in view of the many human interventions required for the operation and maintenance of an NFCF. The safety issues encountered in various NFCFs have been discussed in [8][9]. A comprehensive description of the safety issues of fuel cycle facilities is provided in Ref[11].

For most existing NFCFs, the emphasis is on the control of operations using administrative and operator controls to ensure safety as well as engineered safety features, as opposed to the emphasis on engineered safety features used in reactors. There is also more emphasis on criticality prevention in view of the greater mobility (distribution and transfer) of fissile materials. Because of the intimate human contact with nuclear materials in the process, which may include (open) handling and transfer of nuclear materials in routine processing, special attention is warranted to ensure worker safety. Potential intakes of radioactive materials require control to prevent and minimize contamination and thus ensure adherence to specified operational dose limits. In addition, releases of radioactive materials into the facilities and through monitored and unmonitored pathways can result in significant exposures.

The number of physical barriers in an NFCF that are necessary to protect the workers, the environment and the public depends on the potential internal and external hazards, and the consequences of failures; therefore the barriers are different in number and strength for different kinds of NFCFs (the graded approach). For example, in mining, the focus is on preventing contamination of ground or surface water with releases from uranium mining tails. Toxic chemicals and uranium by-products are the potential hazards of the conversion stage and for forms of in-situ mining. In enrichment and fuel fabrication facilities (with no recycling of separated or recovered nuclear material from spent fuel), safety is focused on preventing criticality in addition to avoiding contamination via low-level radioactive material.

It might be possible to enhance safety features in a nuclear energy system by co-location of front end (e.g. mining/ milling, conversion and enrichment, and fuel production facilities) and back end (reprocessing and waste management) facilities. This would have benefits through minimal transport, optimisation and alignment of processes, avoiding multiple handling of radioactive materials in different plants of the fuel cycle and comprehensive and integrated waste treatment and storage facilities.

Compared to safety of operating NPPs, only limited open literature is available on the experience related to safety in the operation of NFCFs. Examples of United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission regulation are provided in Refs[12][13][14][15][16]. Safety of and regulations for NFCFs have been discussed in IAEA meetings and conferences [8][9]. Aspects of uranium mining have been reported extensively [17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24]. The Nuclear Energy Agency of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development published a comprehensive report on safety of nuclear installations in 2005[25]. Safety guides on conversion/enrichment facilities, fuel fabrication, reprocessing and spent fuel storage facilities have also been published by the IAEA[26][27][28][29][30].

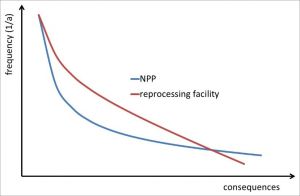

It is obvious that in well-designed NFCFa, the safety related events that have a high hazard potential will have low frequency of occurrence and vice versa. For example, Fig. 1 (modified from Ref[31]) conceptually compares the relationship between potential consequences and frequency for safety related events in a nuclear power plant and a reprocessing facility.

The figure demonstrates that, compared to accidents in an NPP, an NFCF may have relatively higher consequences of accidents having higher probability of occurrence, e.g. accidental criticality. However, accidents with very high consequences have essentially lower probability than in NPPs and can only occur in a few high inventory NFCFs, typically large reprocessing plants and associated liquid high level waste interim storage facilities[32].

Application of the Defence-In-Depth concept to NFCFs

The original concept of defence in depth was developed by the International Safety Advisory Group (INSAG) and published in 1996 [33]. Historically it is based on the idea of multiple levels of protection, including consecutive barriers preventing the release of radioisotopes to the environment, as already formulated in Ref[34]:

“All safety activities, whether organizational, behavioural or equipment related, are subject to layers of overlapping provisions, so that if a failure were to occur it would be compensated for or corrected without causing harm to individuals or the public at large”

The application of DID to NFCFs takes into account their following features:

- The energy potentially released in a criticality accident in a fuel cycle facility tends to be relatively small. However, generalization is difficult as there are several fuel fabrication or reprocessing options for the same or different type of fuels;

- The power density in a fuel cycle facility in normal operation is typically several orders of magnitude less than in a reactor core;

- In a reprocessing facility, irradiated fuel pins are usually mechanically cut (chopped) into small lengths suitable for dissolution and the resultant solution is further subjected to chemical processes. This may create a possibility for larger releases of radioactivity to the environment on a routine basis as compared to reactors;

- The likelihood of a release of chemical energy is higher in fuel cycle facilities of reprocessing, re-fabrication, etc. Chemical reactions are part of the processes used for fresh fuel fabrication as well as for reprocessing of spent nuclear fuel.

The numbers of barriers to radioactive releases to the environment depend in different types of NFCFs on the forms, conditions, inventories and radiotoxicity levels of the processed nuclear materials. Table 3 gives a summary of the typical numbers of barriers to radioactive releases to the environment in existing NFCFs at different steps of nuclear fuel cycle.

| Facility type | Number of barriers | |

|---|---|---|

| Mining | 0–1 | |

| Milling / Processing / Conversion | 1–2 | |

| Enrichment | 2 | |

| Fuel manufacture | Low radioactivity | 1–2 |

| High radiotoxicity | 2–3 | |

| Fresh fuel storage | 2 | |

| Fresh fuel transportation | 2 | |

| Spent fuel transportation | 3 | |

| Spent fuel storage | Wet | 2 |

| Dry | 3 | |

| Reprocessing | 3 | |

| Reprocessing product storage including waste | Low radiotoxicity | 2 |

| High radiotoxicity | 3 | |

Table 4 summarises how INPRO uses the DID concept within this sustainability assessment methodology for the area of NFCF safety. The INPRO methodology applies this DID concept to all NCFCs as part of a graded approach that considers the level of risks in each individual facility.

| Level | DID level purpose[11] | INPRO methodology proposals for NFCFs |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prevent deviations from normal operation and the failure of items important to safety. | Enhance prevention by increasing the robustness of the design, and by further reducing human error probabilities in the routine operation of the plant. Enhance the independence among DID levels. |

| 2 | Detect and control deviations from operational states in order to prevent anticipated operational occurrences at the facility from escalating to accident conditions. | Give priority to advanced monitoring, alarm and control systems with enhanced reliability and intelligence. Together with qualified procedures for operators, the systems need to be able to anticipate and detect abnormal operational states, prevent their progression and restore normalcy. Enhance the independence among DID levels. |

| 3 | Prevent releases of radioactive material and associated hazardous material or radiation levels that require off-site protective actions. | Decrease the expected frequency of accidents. Achieve fundamental safety functions by an optimized combination of inherent safety characteristics, passive safety features, automatic systems and operator actions; limit and mitigate accident consequences; minimize reliance on human intervention, e.g. by increasing grace periods. Enhance the independence among DID levels. |

| 4 | Mitigate the consequences of accidents that result from failure of the third level of DID and ensure that the confinement function is maintained, thus ensuring that radioactive releases are kept as low as reasonably achievable. | Decrease the expected frequency of severe plant conditions; increase the reliability and capability of systems to control and monitor severe accident sequences; reduce the characteristics of the source term of the potential emergency off-site releases of radioactivity Avoid ‘cliff-edge’ failures of items important to safety. Enhance the independence among DID levels. |

| (5) | Mitigate the radiological consequences and associated chemical consequences of releases or radiation levels that could potentially result from accidents. | Emergency preparedness is covered in another area of the INPRO methodology called Infrastructure[35]. |

Necessary INPUT for a sustainability assessment in the area of safety of nuclear fuel cycle facilities

Definition of a nuclear energy system to be assessed

In principle, a clear definition of the nuclear energy system (NES) is needed for an assessment using the INPRO methodology in all its areas. As described in the overview manual of the INPRO methodology , the NES is supposed to be selected, in general, based on an energy planning study. This study is expected to define the role of nuclear power (the amount of nuclear capacity to be installed over time) in an energy supply scenario for a country (or region or globally). Using the results of such a study, the next step is to choose the facilities of the selected NES that fit the determined role of nuclear power in the country (or region). The NES definition should include a schedule for deployment, operation and decommissioning of the individual facilities.

For a NES sustainability assessment in this area of the INPRO methodology, the NFCF to be assessed and a reference design have to be defined. Where possible, the reference design has to be determined as an NFCF of most recent design operating in 2013, preferably from the same designer as the assessed facility, and complying with the current safety standards. In such a case, the INPRO assessment in this area is expected to demonstrate an increased safety level to achieve long term sustainability in the assessed NFCF in comparison to the reference design. If a reference design cannot be identified within the same technology lineage, a similar existing comparable technology or, when other options are not available, an existing facility of different technology used for the same purpose can be used as a reference. If a reference design cannot be defined, it needs to be demonstrated through the assessment of RD&D results that the NFCF design employs the best international practice to achieve a safety level comparable to most recent technology and that the assessed facility is therefore state of the art.

INPRO assessment by a technology user

An INPRO assessor, being a technology user, needs sufficiently detailed design information on the NFCF to be assessed. This includes information relating to the design basis of the plant, engineered safety features, confinement systems, human system interfaces, control and protection systems, etc. The design information needs to highlight the structures, systems and components (important to safety) that are of evolutionary or innovative design[36] and this could be the focus of the INPRO assessment.

In addition to the information on the NFCF to be assessed, the INPRO assessor needs the same type of information on a reference plant design in order to perform a comparison of both designs. Details of the information needed are outlined in the discussion of the INPRO methodology criteria in the following sections.

If not available in the public domain, the necessary design information could be provided by the designer (potential supplier). Therefore, a close co-operation between the INPRO assessor as a technology user and the designer (potential supplier) is necessary as detailed in the INPRO methodology overview manual.

In addition, all relevant operational and maintenance data and history of the reference facility will be useful as well as any records of modifications, any failures and incidents in the reference NFCF or similar facilities.

Results of safety assessments

To assess sustainability, the INPRO assessor will need access to the results of a safety assessment of a reference plant and to the basic design information of the NFCF to be assessed that includes a safety analysis that evaluates and assesses challenges to safety under various operational states, AOO and accident conditions using deterministic and probabilistic methods; this safety assessment is supposed to be performed and documented by the designer (potential supplier) of the NFCF to be assessed.

For an NFCF to be assessed using the INPRO methodology, the safety assessment would need to include details of the RD&D carried out for advanced aspects of the design. Such information is usually found in a (preliminary) safety report (or comparable document) that may be available in public domain or could be provided by the designer (potential supplier) of the NFCF. Thus, as stated before, a close co-operation between the INPRO assessor as a technology user and the designer (potential supplier) is necessary.

INPRO assessment by a technology developer

In principle, an INPRO assessment can be carried out by a technology developer at any stage of the development of an advanced NFCF design. This assessment can be performed as an internal evaluation and does not require results of the formal safety assessment. However, it needs to be recognized that the extent and level of detail of design and safety assessment information available will increase as the design of an advanced NFCF progresses from the conceptual stage to the development of the detailed design. This will need to be taken into account in drawing conclusions on whether an INPRO methodology sustainability requirement for safety has been met by the advanced design.

One potential mode for the technology developer’s use of the INPRO methodology is in performing a limited scope assessment. Limited scope INPRO assessments can be focused on specific areas and specific nuclear energy system installations having different levels of maturity. A limited scope study may assess the facility design under development and may help highlight gaps to be closed in on-going RD&D studies and define the scope of data potentially needed to make future judgements on system sustainability.

Other sources of INPUT

The assessor can use the IAEA Fuel Incident Notification and Analysis System (FINAS) and other international and national event reporting systems for specific and general information relevant to the technology type and detailed design of an advanced NFCF.

[ + ] Assessment Methodology | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||

References

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Regulations for the Safe Transport of Radioactive Material, IAEA Safety Standards Series No. SSR-6 (Rev. 1), IAEA, Vienna (2018).

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Advisory Material for the IAEA Regulations for the Safe Transport of Radioactive Material, IAEA Safety Standards Series No. TS-G-1.1 (Rev. 1), IAEA, Vienna (2008).

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Planning and Preparing for Emergency Response to Transport Accidents Involving Radioactive Material, IAEA Safety Standards Series No. TS-G-1.2 (ST-3), IAEA, Vienna (2002).

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Compliance Assurance for the Safe Transport of Radioactive Material, IAEA Safety Standards Series No. TS-G-1.5, IAEA, Vienna (2009).

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, The Management System for the Safe Transport of Radioactive Material, IAEA Safety Standards Series No. TS-G-1.4, IAEA, Vienna (2008).

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Radiation Protection Programmes for the Transport of Radioactive Material, IAEA Safety Standards Series No. TS-G-1.3, IAEA, Vienna (2007).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 UNITED NATIONS, Our Common Future (Report to the General Assembly), World Commission on Environment and Development, UN, New York (1987).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Safety of and Regulations for Nuclear Fuel Cycle Facilities, Technical Committee meeting in Vienna (2000), IAEA-TECDOC-1221, IAEA, Vienna (2001).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 RANGUELOVA, V., NIEHAUS, F., et al, Safety of Fuel Cycle Facilities, Topical Issue Paper No.3 in Proceedings of International Conference on Topical Issues in Nuclear Safety, Vienna, 3-6 Sept. 2001, IAEA, STI/PUB/1120, IAEA, Vienna (2002).

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Procedures for Conducting Probabilistic Safety Assessment for Non-Reactor Nuclear Facilities, IAEA-TECDOC-1267, IAEA, Vienna (2002).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Safety of Nuclear Fuel Cycle Facilities, IAEA Safety Standards, Specific Safety Requirements No. SSR-4, IAEA, Vienna (2017).

- ↑ NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION, Standard Review Plan for the Review of a License Application for a Fuel Cycle Facility, NUREG-1520 Rev.1. US NRC, Washington (2010).

- ↑ NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION, Standard Review Plan for the In-Situ Leach Uranium Extraction License Application, NUREG-1569. US NRC, Washington (2003).

- ↑ NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION, Consolidated Guidance about Material Licensees, NUREG-1556 series. US NRC, Washington (1998).

- ↑ NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION, Integrated Safety Analysis Guidance Document, NUREG-1513. US NRC, Washington (2001).

- ↑ NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION, Risk Analysis and Evaluation of Regulatory Options for Nuclear By-product Materials Systems, NUREG/ CR-6642. US NRC, Washington (2000).

- ↑ NTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Treatment of Liquid Effluent from Uranium Mines and Mills, IAEA-TECDOC-1419, IAEA, Vienna (2005).

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, The Long Term Stabilization of Uranium Mill Tailings, IAEA-TECDOC-1403, IAEA, Vienna (2004).

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Occupational Radiation Protection, Safety Guide, IAEA Safety Standards No. GSG-7, IAEA, Vienna (2018).

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Monitoring and Surveillance of Residues from the Mining and Milling of Uranium and Thorium, Safety Reports Series No. 27, IAEA, Vienna (2003).

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Management of Radioactive Waste from the Mining and Milling of Ores, Safety Guide, IAEA Safety Standards Series No. WS-G-1.2, IAEA, Vienna (2002).

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Guidebook on Good Practice in the Management of Uranium Mining and Mill Operations and the Preparation for their Closure, IAEA-TECDOC-1059, IAEA, Vienna (1998).

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Innovations in Uranium Exploration, Mining and Processing Techniques, and New Exploration Target Areas, IAEA-TECDOC-868, IAEA, Vienna (1996).

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Guidebook on Environmental Impact Assessment for In Situ Leach Mining Projects, IAEA-TECDOC-1428, IAEA, Vienna (2005).

- ↑ OECD/NUCLEAR ENERGY AGENCY (NEA), The Safety of the Nuclear Fuel Cycle, Third Edition, NEA No.3588, OECD/NEA, Paris (2005).

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Safety of Conversion Facilities and Uranium Enrichment Facilities, IAEA Safety Standards, Specific Safety Guide No. SSG-5, IAEA, Vienna (2010).

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Safety of Uranium Fuel Fabrication Facilities, IAEA Safety Standards, Specific Safety Guide No. SSG-6, IAEA, Vienna (2010).

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Safety of Uranium and Plutonium Mixed Fuel Fabrication Facilities, IAEA Safety Standards, Specific Safety Guide No. SSG-7, IAEA, Vienna (2010).

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Storage of Spent Nuclear Fuel, IAEA Safety Standards, Specific Safety Guide No. SSG-15, IAEA, Vienna (2012).

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Safety of Nuclear Fuel Reprocessing Facilities, IAEA Safety Standards, Specific Safety Guide No. SSG-42, IAEA, Vienna (2017).

- ↑ UEDA, Y., Current Studies on Utilization of Risk Information for Fuel Cycle Facilities in Japan, Workshop on Utilization of Risk Information for Nuclear Safety Regulation, Tokyo, May (2005).

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Experiences and Lessons Learned Worldwide in the Cleanup and Decommissioning of Nuclear Facilities in the Aftermath of Accidents, IAEA Nuclear Energy Series No. NW-T-2.7, IAEA, Vienna (2014)

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Defence in Depth in Nuclear Safety, INSAG-10, A report by the International Safety Advisory Group, IAEA, Vienna (1996).

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, Basic Safety Principles for Nuclear Power Plants, 75-INSAG-3, Rev.1, INSAG-12, IAEA, Vienna (1999).

- ↑ INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, INPRO Methodology for Sustainability Assessment of Nuclear Energy Systems: Infrastructure, IAEA Nuclear Energy Series, No. NG-T-3.12, IAEA, Vienna (2014).

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedr41